We appreciate all of your support this year!

Friday, December 27, 2024

Wednesday, December 25, 2024

Vintage Customs of the 12 Days of Christmas

The 12 Days of Christmas, celebrated from December 25 (Christmas Day) to January 5 (Twelfth Night), are steeped in vintage customs and traditions that vary across cultures and time periods. Here are some notable customs. Maybe you can revive one this year!

1. Christmas Day (December 25)

- Families celebrated with a large feast, often including roast meats, puddings, and special desserts.

- Groups of carolers would sing door-to-door, spreading festive cheer.

- Acts of giving to the poor were common, reflecting the spirit of goodwill.

2. St. Stephen's Day (Boxing Day, December 26)

- People would give boxes of money or goods to servants, tradespeople, and the less fortunate.

- Groups in Ireland would parade through the streets carrying a wren, a symbol of martyrdom, as part of a ritual.

3. Day of the Holy Family

- This day focused on spending time with family, reflecting on the bonds and shared blessings.

4. Feast of the Holy Innocents (December 28)

- Traditions often involved blessing children or giving them small gifts in memory of the biblical massacre of the innocents by King Herod.

5. Traditional Games and Wassailing

- Singing and toasting with a spiced cider or ale to ensure a good harvest and well-being, called “wassailing”. This might involve blessing apple trees.

6. Gift Giving Over the 12 Days

- In some cultures, instead of giving all gifts on Christmas Day, they were spread out over the 12 days, reflecting the song "The 12 Days of Christmas."

7. Twelfth Night Revelry (January 5)

- A special cake was baked with a hidden bean or coin inside. The person who found it would be crowned the "King" or "Queen" of the feast.

- Twelfth Night parties often featured revelers in costumes or masks.

- Performers or "mummers" would enact traditional plays, often centered around themes of renewal and good versus evil.

8. Epiphany (January 6)

- Families would mark their doorways with chalk to bless their homes for the year ahead.

- Sacred water might be blessed and sprinkled around the home.

9. Burning of the Yule Log

- Traditionally, a Yule log would be burned in the fireplace throughout the 12 days as a symbol of warmth and light. Ashes were often kept as charms for good luck.

10. Decorations Left Up

- Christmas decorations were traditionally kept up until the end of the 12 days. Removing them before Twelfth Night was considered bad luck.

11. Feasting and Merriment

- Each day was an opportunity for communal meals, storytelling, and singing. Wealthier households hosted lavish parties.

12. Focus on Spiritual Reflection

- Many customs involved attending church services or reflecting on the meaning of the Nativity and Christ’s life.

#1 Amos J. Dye (1847-1905) - Judge and Ohio State Legislator

Amos J. Dye was born April 2, 1847, in Marietta, Ohio. He was the son of Amos J. Dye, Sr., and Maria Taylor. In 1860, the Dyes owned a large and valuable tobacco farm.

On 18 January 1864, at the age of eighteen, Amos enlisted in

the Union army and was assigned to Company H, 77th Ohio Volunteer

Infantry. Just a few weeks thereafter,

he married Marinda Jane McCowan on February 11, 1864.

On January 1, 1865, he transferred to Company D, 77th Ohio

Volunteer Infantry. He was discharged

March 8, 1866 in Brownsville, Texas, with the rank of private. Possibly his unit went there after the Civil

War as part of the Reconstruction effort.

Amos Dye and Marinda had a son, Herbert, in 1867, and a

daughter, Ida, in 1868. He was admitted

to the Ohio bar as a lawyer in 1877. By

1880, the Dyes were living in Huntington, West Virginia, where Amos was

practicing law.

Marinda died of stomach cancer in May, 1894, in Cincinnati,

Ohio, where she had been active in a fraternal society called the Knights and

Ladies of Honor. Amos Dye himself was by

then a Mason, and a Republican state legislator. Soon, he became an attorney for the Ohio

State Dairy and Food Department.

Dye married Ida Selma Schaetzle, a divorcee, on December 12,

1895. A son named Amos was born in 1897

and a daughter, Selma, in 1901. Another

son, Stelman, seems to have died in infancy.

In 1896, Amos Dye was accused of accepting a $5000 bribe

from a representative of the Paskola Company on condition that the state would

not prosecute a case against the company.

Dye vigorously denied taking a bribe and countersued. Apparently he did not lose his state position

since he continued to handle cases.

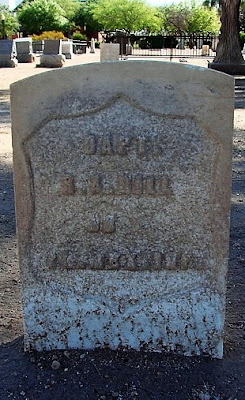

Tiring of Ohio winters, Dye purchased the Rumney house on Grand Avenue in 1902 and thereafter, the Dyes spent their winters in Phoenix. The Dye family was living a mile and a half north of Grand Avenue when Amos died on December 30, 1905, of cardiac insufficiency. He was buried in the Masons Cemetery, Block 17, Lot 3, Grave 3.

Dye’s widow Ida was left to raise their two surviving children alone. She filed for a widow’s pension on February 17, 1906, but her application was rejected on the grounds that Dye’s cause of death was not the result of his military service. She did not remain alone for long, though. Sometime in 1908, she married Peter William De Jong. Ida lived until 1954.

-by Donna Carr

Tuesday, December 24, 2024

#2 Baldomedo Peralta (abt 1852-1903) - A Christmas Eve Tragedy

Descendants of Baldomedo Peralta believe that he was born in Rio De San Pedro, Cuevas de Batuco, Sonora, Mexico. He may have been the son of a Pedro Peralta. His birth year seems to have been somewhere between 1849 and 1854, but verifiable records do not begin until he arrived in Phoenix in 1880.

Apparently, Peralta and Guadalupe Baldenegro had been

keeping company since at least 1879.

They were on their way by wagon train from Superior to Phoenix in

August, 1880, when their first child, Rosario, was born at a wagon stop called

La Poste (now Apache Junction).

Upon reaching Phoenix, the couple was married on September 19, 1880, in a civil ceremony—possibly because there was no Catholic priest available.

Thereafter, the Peraltas had children at regular intervals. Descendants think there were twelve, although only six lived to adulthood. It is not known for sure where they were all born, although the Peraltas seem to have resided in Phoenix continuously and not migrated back and forth between Mexico and Arizona. A two-year-old daughter, Louisa, died in 1900 and was buried in Rosedale Cemetery. Her older sister Guadalupe, aged 9, died in 1902 and was also buried in Rosedale.

Despite the vagueness of his origins, Baldomedo Peralta

seems to have had some education.

Apparently regarded as ‘white’, he registered to vote in 1884, 1890,

1892, 1894 and 1900. He was active in a

Latino mutual-aid society and was also a member of Phoenix’s volunteer fire

brigade.

On Christmas Eve, 1903, the Peralta family was enjoying a festive meal at their home when a kerosene lamp exploded, setting fire to the room. Although the family ran outside into the yard, Baldomedo and Guadalupe quickly realized that one of the children was missing. Peralta reentered the burning house, located the child and passed him through an open window to the family outside. He then attempted to save some of the family’s belongings. When he emerged from the house, his hair and clothing were on fire. Although he stanched the blood flowing from a vein in his neck and walked to a doctor to be bandaged, his burns turned out to be more severe than was first thought. He was admitted to Sisters’ Hospital, where he died on December 27th. He was buried in the Catholic section of Loosley Cemetery.

After Baldomedo’s death, the oldest Peralta son, Porfirio, became the head of the family. He too would eventually join the fire brigade. Porfirio and his family remained in Phoenix until 1921, when they followed some of the other Peralta siblings to California.

- by Donna Carr

Monday, December 23, 2024

#3 Angeline “Angie” Piper (1876-1899) - Schoolteacher

Angeline Piper was born 1876 in Kansas to Ray Piper and Sarah née Fortney. Angie’s parents had been married in Bourbon, Kansas, on October 22, 1874. Angie had a younger brother John, who was born in 1878, but he died in 1881. Nearly two years later, Angie’s father also died, leaving her mother to raise Angie and her sister Raye, born after Mr. Piper’s death. Since Angie’s mother did not remarry, perhaps she had sufficient means to raise two children on her own.

In 1887, a rabid dog bit Angie, her mother and sister. According to one news report, only a “mad stone” (a bezoar stone found in the digestive tract of some animals) would save them from contracting rabies. One was found in Chetopa, Kansas, and all must have gone well, as they all survived.

In April 1898, Angie became quite sick while teaching in Fort Scott, Kansas, and her mother was sent for. Under her mother’s care, Angie recovered and, in November, her mother left for Arizona to visit relatives. Angie remained in Fort Scott at the home of an uncle, but later joined her mother in Arizona.

Angie went to Arizona primarily to recuperate. Unfortunately, she developed typhoid fever and died December 30, 1899. Although she was initially buried in Rosedale Cemetery, her mother later had her remains moved to the IOOF Cemetery when Angie’s Royal Neighbors Society insurance policy paid out.

by Patricia G.

#4 John “Sailor Jack” Twentyman, 1824-1901 An English Seaman in Arizona

John Twentyman was born England in September, 1823. In his youth, he had been a sailor, landing in California just as the Gold Rush was beginning. Thereafter, he engaged in mining, ranching and driving a stagecoach. He was said to have discovered the Sailor Jack mine in Oregon.

Around 1876 he came to Phoenix, where he was employed by ranchers such as W. W. Cook, the Alkire brothers and Jack Miller. During the 1890s, he appears to have moved to Prescott for a couple of years, for he registered to vote there.

In early November, 1900, Sailor Jack, then aged 76, was assaulted and robbed by two gunmen who held up Goddard’s Station on the Black Canyon road. This incident seems to have weighed upon his mind and he decided to move into a room in Phoenix. Jack was said to have been a kind-hearted soul; although he had no known relatives, he had many friends and acquaintances with whom to pass the time of day.

With advancing age came ill health. Despondent, Sailor Jack committed suicide on December 27, 1901. While at the Anheuser Saloon in Phoenix, he slipped out back for a moment to ingest a lethal dose of strychnine. He then reentered the saloon and sat calmly until a single convulsion signaled his demise. According to the coroner, a bottle of strychnine was found in his pocket but no money, although he was known to have had some the day before. Possibly he had given it away.

Mr. Twentyman was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, Block 12, Grave 6.

-by Donna Carr

Friday, December 20, 2024

#5 Alexander D. Cole (1839-1907) - Union Veteran

Alexander D. Cole was born May 17, 1839, in Moosup, Connecticut, to Caleb Cole and Hannah Crandall. The Coles were fairly prosperous farmers.

In October 1862, Cole enlisted in Company A, 12th Rhode Island Infantry, for a period of nine months. His regiment took part in the Battle of Fredericksburg that December. After that, it was on guard duty in Kentucky and Ohio. Cole reenlisted at the end of his initial hitch and served until July 29, 1865.

On January 16, 1868, Alexander Cole wed Ella Augusta Lord in Boston, Massachusetts. The young couple was living in Southbridge, Massachusetts, when their first child, Fannie, was born on November 20, 1869. Alexander was employed in a woolen mill.

Although little Fannie thrived, the Coles’ next three children—Charles, Henry and Gertrude—did not live long enough to see their first birthdays. It wasn’t until October 28, 1876, that Ella gave birth to a son, George Elbert, who would grow to adulthood. One more child, Nellie, was born May 26, 1882.

Over the years, Alexander and Ella seem to have parted ways, as he is listed as divorced on the federal census of 1900; he gave his occupation as ‘landlord’. He and his two daughters had moved to Phoenix around 1895, possibly because Fannie was suffering from a malady which caused her joints to ossify, limiting her mobility (may have been something like rheumatoid or osteoarthritis).

At first, Fannie was active in the local Presbyterian church and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (W.T.C.U.). In time, however, she was confined to bed, unable to bend her arms and legs. On September 17, 1901, her doctor tried a surgical intervention to ‘break’ her joints, but Fannie died of shock following the operation. After a funeral conducted by Rev. McAfee of the Presbyterian Church, she was buried in Rosedale Cemetery.

While living in Phoenix, Alexander Cole joined the John Wren Owen G.A.R. post. In March, 1907, he applied for an invalid pension and received Certificate #969811. He passed away on October 5, 1907, of cardiac dilation, and was buried next to his daughter Fannie in Rosedale.

Nothing further is known of Cole’s younger daughter, Nellie; likely she married. Cole’s son George Elbert lived in Phoenix for a brief time, at least. In 1910, his nine-year-old daughter Ella died of tuberculosis while residing at 716 West Madison. She too was buried in Rosedale, probably in the Cole family plot.

by Donna Carr

Thursday, December 19, 2024

Happy Holidays 2024!

Hi everyone! Just a quick reminder that we will not be open

Thursday, December 26, but we WILL be open:

Saturday, December 28th for Open House from 10 - 1:30

1317 W. Jefferson

Hope we see you all!

And Happy Holidays from us to you, our wonderful friends!!

Wednesday, December 18, 2024

#6 Sgt. John Fraser Cameron (1878-1905) - Veteran of the Spanish American War

John Fraser Cameron, born January 1878 in Memphis, Tennessee, is believed to have been the son of Col. John Fraser Cameron, Sr. and his wife Mary A. Myers. Since John Sr. and his wife died in 1882 and 1883 respectively, it is likely that their six orphaned children were raised by relatives. Three of the Cameron daughters—Mary Belle, Chloe Ann, and Nancy Louise--made advantageous marriages.

John F. Cameron was working as a telephone lineman when he enlisted in the U. S. Army at Galveston on April 28, 1898. It was just a few days after President McKinley had declared war on Spain.

Cameron was regarded as a very good soldier. He rose to the rank of sergeant in Company C, 30th U. S. Infantry and might have made a career in the military, had it not been for his contracting tuberculosis.

He was at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, when he was discharged on May 16, 1905, as unfit for duty. Fort Bayard was a decommissioned frontier fort which was being used as a tuberculosis sanitarium for Army personnel. A week later, Cameron was awarded a disability pension.

Monday, December 16, 2024

#7 Elizabeth “Libbie” H. Taylor (abt 1850-1897) - Immigrant from Canada

Libbie (maiden name unknown) was born in Canada about

1850. At some point, she came to the

United States and married Arthur W. Taylor, born around 1845 in New York

state. There is no evidence that the two

ever had any children.

In

1880, Libbie and her husband were living in Denver, Arapaho County,

Colorado, where Arthur was a molder at

the Colorado Iron Works.

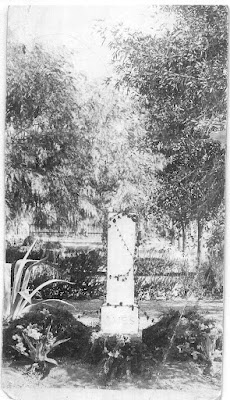

The Taylors were in Phoenix by 1894, but thereafter it appears that Libbie and her husband separated, with Arthur moving to Los Angeles. Though estranged, they nevertheless did not divorce. Apparently Libbie had enough money to be self-sufficient, as she bought several lots in the Churchill addition for $3000, intending to use them as rental properties.

Libbie developed a case of pneumonia and died December 22, 1897, at her home at 27 South Fourth Avenue in Phoenix. Her funeral was postponed until after Christmas as friends sought to reach her husband in California by telegraph. She was buried in Loosley Cemetery, Block 5, Lot 11. One obituary gave her full name as Libbie H. Y. Taylor, possibly indicating she had been previously married.

Shortly

after Libbie’s funeral, her husband returned to Phoenix to take over her

affairs. Mr. Taylor had his late wife’s

remains moved to Porter Cemetery and a large marble monument erected. The plot Libbie is buried in has plenty of

room for other burials, so perhaps he was planning to be buried next to

her.

Since

Libbie had died intestate, a special administrator was appointed to handle her

estate. Notice was given and several

creditors came forward: James M.

Creighton was one of them. Keystone

Pharmacy submitted an unpaid bill for quinine tablets and laudanum, and there

were also bills for nursing and final expenses.

After all of Libbie’s debts had been settled, her husband A. W. Taylor

inherited $4666 in cash and real estate.

Arthur

was last known to be residing in Los Angeles, California, with a family named

Riley and working as a teamster in 1900.

-by Patricia G.

Sunday, December 15, 2024

#8 Margarita Wall Chretin (1882-1904) - A Life Cut Short

Margarita Wall was born February 14, 1882, most likely in Arizona. She was the first-born daughter of Fred Wall and Refugio Rebecca Ramirez. Fred Wall is thought to have been an immigrant from Ireland and sometime miner. A sister, Matilda, was born about four years later, after which her parents parted. Their mother remarried several times thereafter.

On February 15, 1904, Margarita (or Maggie, as she was known), wed Carlos Robledo Chretin in Phoenix, Arizona. Chretin’s unusual surname was due to the fact that his father, Jean-Marie Chretin, was a Frenchman who had married a Mexican woman.

Maggie was probably suffering from tuberculosis already at the time of her marriage. She gave birth to a male infant on December 2, 1904, and died only six days later, on December 8. She was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, with a three-piece marble monument marking her grave.

Maggie’s newborn son was originally named Fred John Chretin. Upon his mother’s death, he was given to his maternal grandmother, Refugio Rebecca Ramirez, who was already nursing an eight-month-old daughter named Ruby O’Leary. Baby Fred’s life was most likely saved because of this steady supply of breastmilk, which also imparted some degree of immunity to childhood illnesses. Fred and Ruby grew up together, and Fred always regarded her as his sister, even though she was actually his half-aunt. Being raised in his grandmother’s household, Fred adopted the surname of her then husband, Daniel O’Leary.

Margaret Chretin’s widower, Carlos Chretin, eventually remarried and had several more children with his second wife, Marta Hernandez. Both the Chretins and the O’Learys moved to Los Angeles around 1918.

Saturday, December 14, 2024

#9 Mary A. List Mosier (1843-1897) - Farmer’s Wife

Mary Ann List was born August 15, 1843, in Pennsylvania. She was the oldest of seven children belonging to David J. List and Ursula Newell.

The Lists had moved to Lee County, Iowa, by 1858, when Mary Ann married Benedict Mosier at the tender age of fifteen. Soon thereafter, the young couple moved to Tyler Township, Hickory County, Missouri, where Mary Ann bore eleven children between 1860 and 1875. Six survived to adulthood. The Mosiers were farmers and, apparently, quite successful ones. Mary Ann’s parents moved to Missouri at about the same time.

In the summer of 1861, Benedict Mosier enlisted in Company C, 8th Missouri State Militia Cavalry, serving in Captain William C. Human’s company. The mission of the regiment was to prevent Confederate forces from establishing a foothold in southwestern Missouri. The soldiers went on numerous scouting patrols and engaged in a few skirmishes. Since Mosier’s duties kept him fairly close to home, he was able to make periodic visits to his family.

Mary Ann’s father, David List, served in the same regiment although he was more than forty years old at the time. He died in Missouri in 1868, leaving his wife and five children.

Although the Mosiers had a productive farm in Missouri, they moved to Arizona around 1884, as did Mary Ann’s widowed mother and several of her siblings. Possibly the Mosiers’ son Sydney was ill and required a warm, dry climate. He died on 30 May 1886 and was buried in City Loosley Cemetery.

Mary Ann undoubtedly lived the life of a farmer’s wife. In addition to the usual household chores, she occasionally worked in the fields and forked hay for the cattle.

Late in life, Mary Ann developed heart problems. In April 1897, she resigned her position as a Sunday School teacher because of ill health. While driving home on 14 December 1897, she apparently suffered a stroke. A neighbor moving cattle noticed that the horse and buggy had stopped in the road and came to her aid, but attempts to revive Mary Ann failed. She too was buried in City Loosley Cemetery.

Following

Mary’s death, Benedict Mosier was much chagrined to learn that Arizona was a

community property state and that Mary’s property would be split between him

and their children. It had never

occurred to him that his late wife owned anything, much less half of the

marital assets.

Mary Ann’s mother, Ursula Newell List, outlived her, dying in Glendale, Arizona, in 1906.

Benedict died on 4 October 1908 and was buried in the family plot in City Loosley.

-by Donna Carr

Friday, December 13, 2024

Jacob Waltz Gravesite Dedication! - January 11, 2025

Save the Date! You are invited to the dedication ceremony

for the Jacob Waltz Gravesite! Lots of time and talents were put into its

beautification for all generations to enjoy. Please RSVP to our email:

pioneercem@yahoo.com. Hope to see you there!

Wednesday, December 11, 2024

Vendors Donate to PCA!

Monday, December 9, 2024

#10 Tallman Jacob "T.J" Trask (1852-1894) - Pioneer Grocer

Tallman Jacob Trask was born 1852 in Vassalboro, Maine, one

of eleven children born to William Chase Trask and his second wife, Sophia

Winslow. By 1860, the Trask family had moved to Concord, Illinois.

When he was 17, Tallman, or T. J. as he was known, went to

work for Abel Gum as a clerk in Gum’s dry goods store. T.J. roomed

with the Gum family while he learned the ins-and-outs of the mercantile trade.

Around 1876, young Trask traveled west to Pueblo, Colorado,

where he became the head clerk in the grocery store of John D. Miller.. It

was there that he met Laura E. Cooper, whom he married in July of 1877. The

couple had two children born between 1878 and 1879, but both died in infancy

and were buried in the Odd Fellows section of the Pueblo Pioneer Cemetery.

In 1879, T. J and Laura moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to

start a new store with Lyman Putney, a business man from Lawrence, Kansas. The

store, which specialized in wholesale groceries and exotic fruits from

California, was located in downtown Albuquerque on Railroad Avenue, opposite

the train depot.

T.J. and Laura had a tumultuous relationship, with Laura

spending much of her time with her family in Pueblo and Kansas. In

the spring of 1884, T. J. filed for divorce on the grounds of desertion. It

was granted in October of 1884. In December of 1884, he married

Lizzie Strother of Ohio, thought by some to have been “an adventuress”. T.

J. dissolved his business interests with his partner Lyman Putney and moved to

Phoenix, Arizona, where he opened a store with his new brother-in-law, Emory

Kays.

Still later, in 1892, T.J. opened another store with Charles

Kessler and T.J’s brother Alonzo. Located on Washington between modern-day

Central Ave and 1st Avenue in Phoenix, the Trask-Kessler wholesale grocery

soon became one of the largest grocery stores in town.

As he prospered, T.J. took on many civic duties, becoming

president of the Arizona Industrial Exposition Association and territorial

fair. His most notable exhibits were a pagoda made from grains grown

on his farm, and a display of hanging tea cups and saucers from his wholesale

grocery store that spelled “Trask-Kessler”. He also served as

president of the Immigration Union, vice president of the Business Chamber of

Commerce in Phoenix, and was on the board of the Phoenix and Prescott Toll Road

Company.

T. J. died on December 8, 1894, from an intestinal ailment

which he had fought for eight months. He was laid to rest in Porter cemetery.

His headstone is of an unusual Moorish design and describes him as an “upright

businessman”.

-by Val Wilson

Saturday, December 7, 2024

#11 Reuben A. Hill (1839-1905) - Skilled Soldier, But Odd With Money

Reuben A. Hill was born November 5, 1839, in Naples, Cumberland County, Maine. He was the son of John Hill and Rebecca Garland, farmers in the area. Farming did not seem to be in Reuben’s future, however. By 1860, he was already in San Francisco, California, working as a common laborer.

That changed with the outbreak of the Civil War, when Reuben Hill enlisted in the Union Army for a term of three years. On September 29, 1861, he mustered in at Camp Downey, near Oakland, California, as a third corporal in Co. I, 1st California Infantry.

As part of the California Column commanded by Colonel James H. Carleton, Hill’s unit was posted to the New Mexico Territory, where it saw action against the Confederates at Picacho Peak, Arizona. Hill seems to have been an effective soldier. He was promoted to sergeant and then commissioned a captain in Co. K, 1st New Mexico Volunteers (New), at Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory, Feb. 29, 1864. Captain Hill resigned at Fort Union, New Mexico Territory, on February 6, 1866.

After the war, Hill returned to Maine where he married Vesta Marhon Whittier on January 19, 1865, presumably while on leave from his military duties. They remained married until January 1880, when Reuben divorced Vesta so that he could marry a widow, Jane Tyler Burrell Wilson.

Jane later alleged that Hill drank excessively and was abusive. By the time he moved out in 1894, he had spent all of Jane’s money. Destitute, Jane was forced to move in with her married daughter. Although Hill suggested that Jane divorce him, she did not do so—possibly because of the social stigma of being a divorced woman.

Reuben Hill then secured a loan from another widow, Olivia S. W. Payne, with which he purchased a hotel in Strafford, New Hampshire. He remained in New Hampshire until about 1902, when he sold the hotel and moved to Arizona to speculate in mines. Once in Phoenix, Hill was cagey about his past and intimated that he had traveled in Europe on a mission for the U. S. government’s secret service.

On December 7, 1905, Reuben Hill died of a broken neck when thrown from his wagon near his mining property at Cave Creek, Arizona Territory. He was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, North section, Block 168, Grave 7.

Hill’s widow Jane did not learn of his death until her son-in-law saw a notice published in a Boston newspaper. Since she was still legally married to Hill at the time of his death, she applied for and received a widow’s pension based on his Civil War service.

Wednesday, December 4, 2024

#12 Perlina Swetnam Osborn (1821-1912) - Arizona Pioneer

In March 25, 1841, she married John Preston Osborn, a native of Claiborne County, Tennessee. By 1850, they were farming in Morgan County, Kentucky., and already had four children.

Around 1853, the Osborns relocated to Adams County, Iowa. The Civil War was in full swing by 1863, when they moved to Colorado, but they had their sights set on the newly created territory of Arizona. Early in 1864, the Osborns joined a party of emigrants traveling via Santa Fe to northern Arizona. They arrived in Prescott on July 6, 1864, with three or four ox teams and wagons loaded with flour, ham and bacon which they sold to Prescott’s hungry miners. With flour selling at $1 a pound and bacon at $.75 a pound, they soon had enough capital to begin their family’s new life in Arizona.

The Osborns built Osborn House, one of Prescott’s first hotels, which provided modest accommodations with a menu of pork and beans, bread and coffee. Perlina, by now expecting her tenth child, remained in Prescott to run it while John Preston explored Del Rio and the Verde Valley and tried his hand at farming and ranching. Unfortunately, his attempts came to naught as the local Yavapai tribesmen repeatedly raided his livestock and crops.

The Osborns’ oldest children having reached marrying age, daughter Jenettie wed Joseph Thomas Barnum in 1865, and Louisa married an up-and-coming lawyer named John Alsap on June 6, 1866. However, the alliance was short-lived as she died barely a year later.

The Osborn's son, John Jr., along with his erstwhile brother-in-law, John Alsap, moved south to the Salt River Valley in 1869, and John Sr. and Perlina joined them in January 1870, establishing a homestead at what would become McDowell and Seventh Street.

Once again, the Osborns were among the first white families to settle in a pioneer town. John Preston, now in his sixties, became an influential citizen of the new town. Perlina was known for her nursing skills, and the Osborns hosted many a traveling minister during Phoenix’s early years.

When John Preston Osborn died on January 19, 1900, he was buried in the A.O.U.W. Cemetery. Around the time of Osborn's death, the street that ran along the south side of the Osborns' farm became known as Osborn Road, a tribute to this pioneer family.

Perlina passed away on December 3, 1912, at the age of 91.

-by Donna Carr

12 Graves of Christmas: Honoring Our December Pioneers

This December, we will commemorate 12 pioneers from our historic cemetery who passed away during this month. Through this countdown, we honor their contributions to our community, reflect on the challenges they faced, and remember the impact they had during their time.

While some of their stories are somber, they are an important part of our history, reminding us of the resilience and humanity of those who came before us. Join us in this journey of reflection and remembrance as we count down the 12 days, preserving their memory during this season of reflection and giving.

Monday, December 2, 2024

Sarah Maddox (1890-1911) - Lovelorn Schoolgirl

She may have been the daughter of John Wesley Maddux, a white man who owned a saloon in Happy Camp, California, and his first wife, a local Native American woman. John Wesley Maddux did have a daughter named Sarah, but little else is known about her.

While at school, Sarah apparently fell in love with a young man who was a member of the school’s baseball team. Being shy, she hoped to attract his attention by appearing on stage in the school’s dramatic productions. One such performance took place late in February, 1911, and all confirmed that she did an outstanding job. However, Sarah was bereft to learn that the object of her affections had not even been present to witness her triumph.

Feeling rejected, Sarah swallowed a caustic compound—possibly lye or mercury—and died about two weeks later from the painful effects. She was buried in Rosedale Cemetery.

It is not known whether the young baseball player ever knew of her interest in him.

- by Donna Carr

Friday, November 29, 2024

Vintage Thanksgiving Customs to Revive This Holiday Season

Pie Socials with Neighbors

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, post-Thanksgiving

evenings were often spent visiting neighbors for "pie socials."

Families would bring their leftover desserts to share while catching up with

friends. It was a relaxed and delicious way to wind down the holiday.

How could you revive it?

Host a mini pie party with leftover slices, or turn it into a potluck

dessert swap. Light some candles, play vintage music, and enjoy the cozy vibes.

Storytelling by the Fire

Before television, families gathered by the fireplace to

share stories. Elders would recount tales from their youth, and children would

chime in with their own whimsical creations. These sessions were rich with

laughter, learning, and love.

How could you revive it?

Set up a storytelling circle with family or friends. Ask older family

members to share their Thanksgiving memories, or take turns creating a

collaborative story.

Leftover Feasts

Late-night snacks were a beloved tradition. Families would

gather for a second, smaller meal of turkey sandwiches, pickles, and pies.

These impromptu feasts were about savoring the holiday flavors one last time.

How could you revive it?

Take leftovers to work or school, or even better, take a picnic lunch

with friends and family to the cemetery.

You can visit and celebrate with your loved ones there too, both past

and present.

Thanksgiving Scrapbooking

Victorian families loved creating keepsakes of their

holidays. They often documented Thanksgiving by pressing autumn leaves, writing

reflections, or sketching scenes from the day.

How could you revive it?

Start a Thanksgiving scrapbook. Collect mementos like photos, pressed

leaves, or handwritten notes of gratitude from family members. Add to it each

year for a cherished family heirloom.

The days after Thanksgiving can be used by embracing vintage

customs that make the holiday even more meaningful. By revisiting these

nostalgic traditions, you can create a warm, connected, and memorable

experience for everyone around you

What are your favorite post-Thanksgiving traditions? Share

in the comments, and don’t forget to pin this post for inspiration next year!

Thursday, November 28, 2024

Monday, November 25, 2024

Alfred Scott (1881-1906) - Phoenix Indian School Student

Opened in 1890, the Phoenix Indian School was intended to function as a residential industrial school and to teach Native American teens and young adults useful occupations such as carpentry, animal husbandry and the domestic arts--sewing, cooking, nursing. In time, its dormitories housed a total of about 700 pupils from 35 different tribes, including some advanced students from other Western states.

The school was designed to be a self-sufficient as possible. Vegetables were raised in the gardens. Male students tended the cows in the dairy and made the furniture used in the classrooms and dormitories. Female students sewed school uniforms and practiced some native crafts such as basket-weaving.

In addition to classes in occupational skills, the school had an academic curriculum similar to that taught in the average high school of the time. Many of the teachers were themselves Native Americans from tribes elsewhere in the United States, on the theory that they would serve as relatable role models. The school newspaper was produced in the campus print shop, and the school’s military drill team, marching band and football and baseball teams were highly regarded. Each fall, students participated in the annual territorial fair, exhibiting handicrafts and taking part in horse races and foot races.

Alfred Scott played left outfield on the school’s baseball team in 1901. In 1904, he gave a declamation entitled “The Road to Placerville”, from Mark Twain’s book Roughing it, at a literary night performance.

On 1905, Alfred married an Anglo schoolteacher, Mae Glase, in Los Angeles, California. They had met while Miss Glase was teaching at the Phoenix Indian School. After the wedding, the young couple moved to Fort McDowell, where Mae taught elementary school.

Tragically, Alfred was already suffering from tuberculosis and died less than a year later on 10 April 1906. He was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, and his widow had a red sandstone monument placed on his grave.

Mae Glase Scott eventually moved to Murray, Utah, where she was employed for 33 years as a schoolteacher and principal. She died in Seattle in 1951.

-by Donna Carr

Friday, November 22, 2024

Giving Tuesday - December 3, 2024

Mark the date - December 3! Giving Tuesday is approaching! Please consider us when donating to your favorite charities. We are an all-volunteer organization and 100% of your donations go to preserving these historic cemeteries and their history. Thank you for being our valued members and friends!

Wednesday, November 20, 2024

USDA Military Veteran Gravesite Cleanup Project - Recognizing Our Beloved Military Pioneers

Monday, November 18, 2024

Edna Hillman (1891-1912) - Maidu Schoolgirl

Photo of a Maidu family, 1906 (William

Thunen, photographer)

LCCN 2020635536

Edna Hillman was born around 1891 in Greenville, California, to George

and Maggie Hillman. She is known to have

had two brothers.

Government and school records describe Edna as a full-blood Digger Indian. That was a somewhat pejorative term applied to many tribes that lived in the Great Basin regions of Utah, Nevada and northern California. The area around Greenville was home to the Maidu tribe, so it is likely that she was Maidu.

The Maidu were hunter-gatherers who typically lived in dugouts and subsisted on acorns, game, seeds and edible roots, hence the name. During the Gold Rush years, the Maidu were dispossessed of their lands and decimated by diseases to which they had no immunity.

Her parents having died, Edna was enrolled in a boarding school in California in 1897. She was a Methodist; it is not known whether that was by choice or because the school that took her in happened to be Methodist.

By all accounts, Edna was a good student. Since she was 19 and an orphan, she herself signed the permissions to attend Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania for five years. A Carlisle trade school education was the best available to Native Americans of the turn of the century. Edna’s classes would probably have focused on practical skills such as cooking, sewing and nursing.

When Edna arrived at Carlisle on October 9, 1910, she was 5 feet 1 inch tall and weighed 133 pounds. However, she entered the school’s hospital in August 1911, where she was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Her medical records show what she was fed. She was sometimes nauseous and often refused the milk and eggnog that was pressed upon her (many Native Americans are lactose-intolerant).

By November 1911, Edna was failing rapidly. Having no family left in California to care for her, she asked to be sent to a government sanitarium in Phoenix. She left the school on December 11 but, by the time she reached Phoenix, it was clear that she was too far gone to recover. She died on January 22, 1912, and was buried in Rosedale Cemetery.

-by Donna Carr

.JPG)